Another figurine on the quilt that

can be associated to the culture of Catal Huyuk and Minoan Crete is the Cycladic

Goddess, found on the eponymous neighbouring islands. Interestingly, here she

is seen in a more stylized form than the Snake Goddess just mentioned.

Small-breasted and folding her arms across her breast, with tapered legs and

without clearly defined facial features, she somehow reminds me of the small

25,000 year-old woman dubbed the Venus of Willendorf, again for where she was originally

found by archaeologists – but for me she is the Great Mother, and in my

correspondences she represents the creative fecundity formed in the darkest period of the year,

which gives birth to the light at the winter solstice, transforming and

renewing. In this cycle the Cycladic Goddess furthers the process of renewal at

spring, when the unformed potential held in the dark becomes manifest in

promising buds and blooms.

Another image is that of the Bronze

Age goddess known variously across the ancient territories of Mesopotamia, Sumeria

and Babylonia as Inanna – or Ishtar in later texts. She expresses the joy

resulting from the fecundity of creation, and in the creative process brings

the promised end of renewal into full form, seasonally experienced in the

harvests of summer. Also slightly stylized perhaps, the image shows the abundance

of woman-power for nurturing and sustaining as she hold her breasts in offering

– and maybe celebrations? Where would the human race be without her? Her

perceived role goes back to the Neolithic idea that the ‘creativity of the

goddess was a constant state, brought about by herself in union with herself,

and that the fertility of all aspects of creation was her epiphany.’[1]

Stories about this deity in her various names, forms and attributes are

complex, dealing with both the dark and light side of human experience, but

let’s say just that many of them reflect the ongoing process of moving into and

consolidating a patriarchal mindset. I ‘read’ the image for how I see her

today, to empower my understanding of woman carrying the values of universal

continuity for the human species, as bearer of life, as nurturer and sustainer.

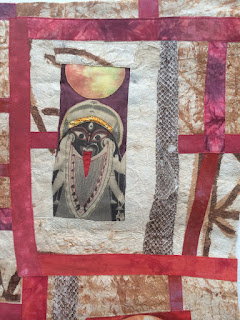

Through the annual sloughing of their

skin, snakes have always been associated with renewal and rebirth, and

therefore with the fecundity of woman; as well as being the guardian and

protector of sacred precincts, including the household. Their natural movements

and instincts also represent a connection between the underworld and the earth.

All of the shrines in the quilt have a section of the skin found by my neighbour

incorporated into them. The significance seems to adapt to that of the Goddess

in each. For example, for Kali Ma it is the end of the creative cycle, as in

her compassion she destroys to create at the season of Autumn in the annual

cycle. In my interpretation of the Goddess correspondences for the Wheel of the

Year, it is her role to sort and separate as she ‘composts what remains from

the harvest and returns it to the dark in preparation for continuity into the

next creative round.’[2]

[1] Anne Baring & Jules Cashford, 1993, The myth of the Goddess: evolution of an image, Penguin Arkana:

London

[2] Annabelle Solomon, 2010, A

creative imaginary for cultural change explored through a feminist spirituality

and women’s textile art. (unpublished PhD thesis), p.149 – 152

http://researchdirect.uws.edu.au/islandora/object/uws:12868