The intention in making this wall-hanging

was as a tribute to my beautiful mentor and friend of 25 years, thea Gaia. Today

is the first anniversary of her passing. Thea had already been working for many

years in the area of women’s spirituality, firstly within the Congregational

(laterUniting) Church as a minister, then stepping outside the rigid

masculinist interpretations of divinity to explore with other women ‘a free and

lively exploration of a female divine in women, nature, the earth, and the

interconnectedness of life.’[1]

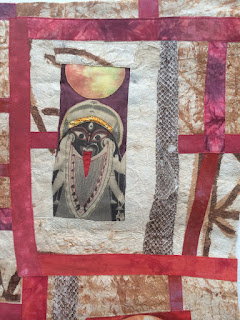

In working on the small shrines for each

image, I wondered why thea had chosen these particular goddesses – and perhaps

more critically about their relevance for today’s woman and today’s world. It

is clear that the images presented in the work do not belong to the same era,

nor do they have the same geographical location, though are generally

associated with civilizations that came and went in the middle/near East. They

do cover a wide area and very broad time-span of spiritual exploration, from

Central Europe 30,000 years before the present era (Venus of Willendorf) to the

last century (Kali) – much older than the patriarchal, Abrahamic religions,

which are less than 3,500 years old, and offering great variety and depth of

understanding.

Reflecting on the title and final presentation

of the work I was aware of the relationship between the materials being used to

construct the wall-hanging, and the valuable relevance of such ancient images

of goddess in today’s societies. The use of natural and perishable materials,

such as tapa, a cloth made by indigenous Pacific islander peoples from plant

fibre, and a sloughed snake skin seemed significant in presenting an idea of

female divinity that perished as a result of the overpowering of those earlier egalitarian,

peaceful societies by a patriarchal mindset, one that set about establishing

and maintaining through religion an ethos of domination over cooperation as the

norm for social interaction. Then modern technology has produced the digitally

printed images. During the time of its making, I began to think about the

enduring presence of these indigenous goddesses from the northern hemisphere.

They have the power to initiate personal and unique explorations of

subjectivity outside the cultural domination preserved by a monotheistic male

mythology for the divine. During the month-long process of construction many

titles came to mind:

“She

is here: I am she”/ Shrines to She /Awesome

Power / Soul Sisters / Bloodlines /Shrines to when God was a woman

Eventually it was settled on: “Before the

beginning, when God was a woman”, using two other titles: the first part is taken from the prologue to Carol Christ's "Rebirth of the Goddess", titled 'Before the beginning', in which she quotes a beautiful poem by Christine Lavadas[2]. (thea, myself and Glenys Livingstone 'performed' this poem at a visit from Elizabet Sahtouris to thea's home when she lived in the Blue Mountains). And the second part is from the

title of a text by one of the earliest spiritual feminist writers, Merlin Stone (1976). Here is the poem:

Evrynome – A Story of Creation

By Christine Lavadas

Long, long in the past, far, far in the

future,

At that point, before the beginning, after

the end,

Where time and space do not exist,

Where all colours and forms are lost in the

blackness of the void.

There was a heavy, vast silence,

A profound eternal motionless,

And nothingness and everything were the

same.

And then Evrynome, Gaia, Goddess of a

thousand names,

Mother of all,

Sighed.

And the sound of her breath echoed

pleasingly in her ears.

As if it were a foreseeing

And yet as if it were a remembrance,

She heard summer breezes ruffling tall

green grasses,

And winter hurricanes howling through deep

valleys,

And the pounding of the sea,

And the calling voices of all creation.

And so Evrynome, Gaia, Goddess of a

thousand names,

Mother of all,

Pursed her lips and whistled for the wind.

Then slowly, smoothly, and with perfect

sensuality

She rose up from the timeless bed of her

infinite rest

And caught up the wind

In her cupped hands,

In her streaming hair,

In the billows of her skirts,

And in the warm secret places of her body,

And she danced.

She danced delicately, she danced

frenziedly,

She danced in staccato rhythm and liquid

movement,

She danced with pure precision and

orgiastic abandon,

She danced gloriously.

She danced holding the wind in her close

embrace,

She danced the love and joy of creation.

She danced and danced.

And from the arch of her foot leapt the

circles of time,

And from the curve of her spine, the

spirals of life,

Day and night,

Black and white,

Absorption, reflection,

Birth, death, resurrection.

And as the ecstasy grew, as the beat

increased,

The wind blew wild and her belly swelled

round.

And from the rivers of her sweat, oceans

flowed,

And with each heave of her breast,

mountains rose.

And when she threw back her hair and opened

her hands,

Life teemed around her and harmony reigned.

Creation now danced in her perfect time

And she smiled.

In spite of their origins, they still have

the power to inform my own sense of being ‘indigenous’ to Earth in the land of

my birth Australia, through my European cultural heritage. We know that the

attitude of the Indigenous Australians to the arrival of the Europeans on their

shores was one of honouring them, in the expectation of a customary reciprocal

and fair exchange.[3] While we

also know that this is not how it has finally played out, the images tend to

awaken another sense of how it might have been. Maybe that’s why these images

remain important, needing to be revived and re-viewed: to remind us of how it

once was - “In the beginning, when god was a woman”, and of the possibility of

how it might be if we go full circle by restoring the female to her awesome

power, through contemporary women. These images live in a continuum encompassing

living women, spirits and ancestors, qualities that are essential governing

principles for a fair, just and egalitarian society. Further paraphrasing the

thoughts of Max Dashu, these goddesses express, embrace, and invite the awe

that is the sense of Mystery aroused by the beauty in nature, art, music and

dance, and the interconnections between self and other - not the mystification

practiced in authoritarian, hierarchical institutions that demand submission

without knowledge[4] (commonly

expressed as having ‘faith’). ‘What is divine can be found within our embodied

selves rather than in a transcendent disembodied theology,’ [5]…and

looking at images of ancient empowered women across time and across the globe

can only help! I feel that thea would agree.

[2] Prologue in Carol Christ, 1997, Rebirth

of the Goddess: finding meaning in feminist spirituality, Addison Wesley

Pub Co: NY

[3] Meyer Eidelson, Melbourne

Dreaming: a guide to important places of past and present, Aboriginal

Studies Press.